Happy Couple II

Happy Couple II

by K. Mas-Gallegos

Collage on paper

10"w x 7"h

Contact K. Mas-Gallegos about this collage

We collage because we don't know how to quilt.

December 9, 2007: Ginger Mayerson has moved to Ginger Mayerson Collage. Please update your bookmarks, thanks!

The first "fine art" use of collage dates to Picasso's 1912 cubist work, "Still Life with Chair Caning" which integrated a chair cane patterned oilcloth into an unusual oval format. Fragments of newspapers and wine labels quickly became part of the fractured surfaces of Picasso and Braque's cubist still lifes adding another dimension to

The first "fine art" use of collage dates to Picasso's 1912 cubist work, "Still Life with Chair Caning" which integrated a chair cane patterned oilcloth into an unusual oval format. Fragments of newspapers and wine labels quickly became part of the fractured surfaces of Picasso and Braque's cubist still lifes adding another dimension to  their multiple viewpoints. Other early movements also found collage a dynamic tool. Russian constructivist artists, such as El Lissitsky, pioneered the art of photomontage for use in their exhibition posters and catalogs. The futurists, a radical Italian group of artists entranced with speed, technology and revolution, created Free Word collages meant to create visual associations with swirling abstractions of cut up and painted words. But it was the surrealists and the Dadaists who trans formed collage into a

their multiple viewpoints. Other early movements also found collage a dynamic tool. Russian constructivist artists, such as El Lissitsky, pioneered the art of photomontage for use in their exhibition posters and catalogs. The futurists, a radical Italian group of artists entranced with speed, technology and revolution, created Free Word collages meant to create visual associations with swirling abstractions of cut up and painted words. But it was the surrealists and the Dadaists who trans formed collage into a  medium of psychological, social and political commentary. The surrealists also titled their collages creating a conundrum between image and text. Several of my favorites of this period are Kurt Schwitters, John Heartfield and Hannah Hoch, all German artists active in the 20s and 30s. The most abstract artist of the three, Schwitters collected found rubbish from the street, combining discarded scraps to poetic and transcendent effect. John Heartfield's incisive, powerful collages savaged Hitler's

medium of psychological, social and political commentary. The surrealists also titled their collages creating a conundrum between image and text. Several of my favorites of this period are Kurt Schwitters, John Heartfield and Hannah Hoch, all German artists active in the 20s and 30s. The most abstract artist of the three, Schwitters collected found rubbish from the street, combining discarded scraps to poetic and transcendent effect. John Heartfield's incisive, powerful collages savaged Hitler's  Germany during the 1930s. Born Helmut Herzfeld, he deliberately anglicized his name to protest the Nazi regime's policies. In one famous collage, "Hurrah, the butter is finished," a complacent German family is seated around a table under a portrait of Hitler. They and the baby in the carriage are devouring bicycle handlebars and metal parts, a response to Goebbel's propaganda of rationing to build the Nazi war machine. Heartfield's photomontages exposed the brutal, corrupt, dangerous nature of the fascists. Also involved with social critique, Hannah Hoch, one of the very few women Dadaists, made elegant. iconic and sensual female portraits that still resonate today.

Germany during the 1930s. Born Helmut Herzfeld, he deliberately anglicized his name to protest the Nazi regime's policies. In one famous collage, "Hurrah, the butter is finished," a complacent German family is seated around a table under a portrait of Hitler. They and the baby in the carriage are devouring bicycle handlebars and metal parts, a response to Goebbel's propaganda of rationing to build the Nazi war machine. Heartfield's photomontages exposed the brutal, corrupt, dangerous nature of the fascists. Also involved with social critique, Hannah Hoch, one of the very few women Dadaists, made elegant. iconic and sensual female portraits that still resonate today.  In the 50s, Robert Motherwell simultaneously created mural scale abstract expressionist pieces along side small collages. He utilized torn posters, labels, his daily mail, cigarette packets, and other detritus of life to create a visual diary of every day living. The term Pop Art came from British artist, Richard Hamilton's small 1956

In the 50s, Robert Motherwell simultaneously created mural scale abstract expressionist pieces along side small collages. He utilized torn posters, labels, his daily mail, cigarette packets, and other detritus of life to create a visual diary of every day living. The term Pop Art came from British artist, Richard Hamilton's small 1956  collage, "Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes, So Different, So Appealing?" a pastiche of advertisements from magazines that included a male body builder holding a tennis racket labeled POP. Among the many pop artists incorporating

collage, "Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes, So Different, So Appealing?" a pastiche of advertisements from magazines that included a male body builder holding a tennis racket labeled POP. Among the many pop artists incorporating  found imagery into their work, Rauschenberg especially has used appropriated topical imagery in mysterious combinations of breathtaking beauty. While Rauschenberg juxtaposes street signs and astronauts, famous people and art historical references into a dizzying visual cacophony of multiple associations, Joseph Cornell's delicate collages and boxes reflect a romantic narrative, vastly different, but just as mysterious.

found imagery into their work, Rauschenberg especially has used appropriated topical imagery in mysterious combinations of breathtaking beauty. While Rauschenberg juxtaposes street signs and astronauts, famous people and art historical references into a dizzying visual cacophony of multiple associations, Joseph Cornell's delicate collages and boxes reflect a romantic narrative, vastly different, but just as mysterious. Today collage is ubiquitous. Any group gallery show will include collages on exhibit. Surrounded as we are by mediated images, it has become the dominant artistic practice. Of Los Angeles contemporary collage artists, two that I especially admire follow the threads of previous movements. David Hockney's gigantic and impressive photo collages are a reworking of the cubist oeuvre. They sparkle with wit

Today collage is ubiquitous. Any group gallery show will include collages on exhibit. Surrounded as we are by mediated images, it has become the dominant artistic practice. Of Los Angeles contemporary collage artists, two that I especially admire follow the threads of previous movements. David Hockney's gigantic and impressive photo collages are a reworking of the cubist oeuvre. They sparkle with wit  as he dissects luncheon guests or gives us the grandeur of an almost anonymous high desert landscape. In another scale, Betye Saar's intimate collages express narrative and social concerns. She tells personal stories of family memories and reference instances of discrimination and racism in beautifully subtle pieces.

as he dissects luncheon guests or gives us the grandeur of an almost anonymous high desert landscape. In another scale, Betye Saar's intimate collages express narrative and social concerns. She tells personal stories of family memories and reference instances of discrimination and racism in beautifully subtle pieces.  Waiter! (pg 11) by K. Mas-Gallegos presents a constructed female form in a pose of supplication with palms open. Mapped on the body are colorful, abstract and serpent designs as well as skeleton parts and an exposed heart: symbols of ancient Aztec culture. The head could be a Latina; her angry shout made more terrifying by the tongue, nose, and eyelid piercing. She rises out of a colorful Carlos Almaraz fragmented landscape and stones press on her head. Victim or goddess? Her grito indicates she will be served. In contrast Ginger Mayerson's

Waiter! (pg 11) by K. Mas-Gallegos presents a constructed female form in a pose of supplication with palms open. Mapped on the body are colorful, abstract and serpent designs as well as skeleton parts and an exposed heart: symbols of ancient Aztec culture. The head could be a Latina; her angry shout made more terrifying by the tongue, nose, and eyelid piercing. She rises out of a colorful Carlos Almaraz fragmented landscape and stones press on her head. Victim or goddess? Her grito indicates she will be served. In contrast Ginger Mayerson's  Corona (pg 37) positions a regal Renaissance female figure between a monumental mountainscape and an overstuffed armchair. The rich earth tones of the figure's clothing, the chair and the mountains are juxtaposed with the cool blue of the sky and the woman's placid expression. The triangular composition of the collage draws your eye to the woman's waiting face and the mountain peak that replicates her crown. Is she trapped between civilization and nature? Is the armchair a throne and the woman the power behind it? The meaning of both collages is illusive and intriguing.

Corona (pg 37) positions a regal Renaissance female figure between a monumental mountainscape and an overstuffed armchair. The rich earth tones of the figure's clothing, the chair and the mountains are juxtaposed with the cool blue of the sky and the woman's placid expression. The triangular composition of the collage draws your eye to the woman's waiting face and the mountain peak that replicates her crown. Is she trapped between civilization and nature? Is the armchair a throne and the woman the power behind it? The meaning of both collages is illusive and intriguing. Addressing a similar theme, Gallegos' Desert Dreams (pg 20) and Mayerson's Traveling Light 2 (pg 53) deal with a fantasy L. A., our journey through it and immigration. Again Gallegos' appropriates from Almaraz, a seminal Chicano artist, emblematic of the L. A. Chicano art scene. Cut outs of his paintings of twisted skyscrapers and a smoking bungalow edge a curved yellow highway, whose line symbolizes the border. A motorcycle and packed station wagon are ready to provide a quick escape for the two women peering at the road and the bridge across, but perhaps they'll climb the ladder instead. This white ladder, reaching up and out of the picture, resembles

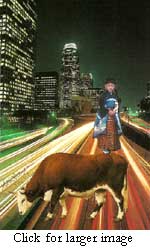

Addressing a similar theme, Gallegos' Desert Dreams (pg 20) and Mayerson's Traveling Light 2 (pg 53) deal with a fantasy L. A., our journey through it and immigration. Again Gallegos' appropriates from Almaraz, a seminal Chicano artist, emblematic of the L. A. Chicano art scene. Cut outs of his paintings of twisted skyscrapers and a smoking bungalow edge a curved yellow highway, whose line symbolizes the border. A motorcycle and packed station wagon are ready to provide a quick escape for the two women peering at the road and the bridge across, but perhaps they'll climb the ladder instead. This white ladder, reaching up and out of the picture, resembles  an oil derrick or a beacon. It serves to visually balance the dark cityscape and signals aspirations and obstacles. Mayerson reads the city differently. In Traveling Light 2, a time exposure night photograph of downtown Los Angeles turns the cars on the freeway into streaks of light in contrast to the office buildings whose lit windows form a black and white checkerboard. In the foreground a steer crosses the light streaked freeway. Standing on its back, a small Asian boy dressed in a ceremonial Japanese kimono so barely touches the steer as to almost float above it. The steer is plodding and tired while the boy is youthful, but serious. Thus, the powerful city of Los Angeles is pictured by Mayerson as the intersection of East and West.

an oil derrick or a beacon. It serves to visually balance the dark cityscape and signals aspirations and obstacles. Mayerson reads the city differently. In Traveling Light 2, a time exposure night photograph of downtown Los Angeles turns the cars on the freeway into streaks of light in contrast to the office buildings whose lit windows form a black and white checkerboard. In the foreground a steer crosses the light streaked freeway. Standing on its back, a small Asian boy dressed in a ceremonial Japanese kimono so barely touches the steer as to almost float above it. The steer is plodding and tired while the boy is youthful, but serious. Thus, the powerful city of Los Angeles is pictured by Mayerson as the intersection of East and West.  In both The Band (pg 65) by Mayerson and Sterile Condo With Drawn Curtains (pg 14) by Gallegos two groups of men confront the viewer. Both black and white photos center the collage, but Gallegos' men are Latinos and Mayerson's are Anglo. Each collage also contains a central female figure. In Gallegos' collage, the draped nude (drawn curtains?) sprawls voluptuously at the feet of the male group. Her face, and therefore her identity are hidden. The surrounding lush fruit and flowers contribute to the sensuality of the prostrate

In both The Band (pg 65) by Mayerson and Sterile Condo With Drawn Curtains (pg 14) by Gallegos two groups of men confront the viewer. Both black and white photos center the collage, but Gallegos' men are Latinos and Mayerson's are Anglo. Each collage also contains a central female figure. In Gallegos' collage, the draped nude (drawn curtains?) sprawls voluptuously at the feet of the male group. Her face, and therefore her identity are hidden. The surrounding lush fruit and flowers contribute to the sensuality of the prostrate  figure. Yet the whole collage creates a disturbing dissonance between the vulnerable, adoring woman in living color (nature) and the tough guys in graphic black and white who ignore her to gaze confidently at the viewer. The shadowy grey Ferris wheel background and the negative head shapes echo the group photo's mechanical quality. The composition is like a religious last supper with the white dove Holy Ghost hovering above. To me, this collage is an indictment of the unequal relationships in patriarchal culture. The opposite is occurring in Mayerson's fantasy collage The Band. Although the four male figures stare at the viewer, they share equal picture space with a fanciful cat woman. Taking off her mask, she sticks out her long red tongue, her voluminous black strapless dress floating on the water with four little illuminated houses. The men here are stuck on shore. In their black and white photo faded to grey, they exist in a misty, rural landscape. They subserviently wait for the cat queen to signal that they should strike up the band and play to her tune.

figure. Yet the whole collage creates a disturbing dissonance between the vulnerable, adoring woman in living color (nature) and the tough guys in graphic black and white who ignore her to gaze confidently at the viewer. The shadowy grey Ferris wheel background and the negative head shapes echo the group photo's mechanical quality. The composition is like a religious last supper with the white dove Holy Ghost hovering above. To me, this collage is an indictment of the unequal relationships in patriarchal culture. The opposite is occurring in Mayerson's fantasy collage The Band. Although the four male figures stare at the viewer, they share equal picture space with a fanciful cat woman. Taking off her mask, she sticks out her long red tongue, her voluminous black strapless dress floating on the water with four little illuminated houses. The men here are stuck on shore. In their black and white photo faded to grey, they exist in a misty, rural landscape. They subserviently wait for the cat queen to signal that they should strike up the band and play to her tune. Gallegos and Mayerson switch approaches to the representation of women with fluidity as my one last comparison of their incisive observations will show. In Mayerson's Girlfriends, (pg 67) three women (two portraits from art history) pose in front of a huge hydroelectric dam with traffic streaming below. The three girlfriends do not smile or even interact with each other. Only one gazes out at the viewer. The other two are demurely looking out of the picture plane past their friend. In front of the three floats a fish bowl with gold fish swimming. The women, like the fish, are contained; their power restrained like the dam in the background. This is not a happy picture. On the other hand,

Gallegos and Mayerson switch approaches to the representation of women with fluidity as my one last comparison of their incisive observations will show. In Mayerson's Girlfriends, (pg 67) three women (two portraits from art history) pose in front of a huge hydroelectric dam with traffic streaming below. The three girlfriends do not smile or even interact with each other. Only one gazes out at the viewer. The other two are demurely looking out of the picture plane past their friend. In front of the three floats a fish bowl with gold fish swimming. The women, like the fish, are contained; their power restrained like the dam in the background. This is not a happy picture. On the other hand,  Barbarian in a Bowtie (pg 24) by Gallegos is a hoot. At first glance I did not see the Viking hat with the horns and mistook the man for a portrait of Henry VIII. How appropriate I thought! He's lost his head and Marie Antoinette has kept hers. Whatever. The woman dominates his tiny figure with her out of scale head and hand. Seated in a posh interior, they strike a casual movie star pose. Their glittering consumerism is reflected in her starry eyes. They make the perfect L. A. couple.

Barbarian in a Bowtie (pg 24) by Gallegos is a hoot. At first glance I did not see the Viking hat with the horns and mistook the man for a portrait of Henry VIII. How appropriate I thought! He's lost his head and Marie Antoinette has kept hers. Whatever. The woman dominates his tiny figure with her out of scale head and hand. Seated in a posh interior, they strike a casual movie star pose. Their glittering consumerism is reflected in her starry eyes. They make the perfect L. A. couple.